My Personal Journey

By Michael Alvear, Health Author & Independent Researcher

My research is published on these scholarly platforms:

Last Updated:

I’m a writer. Nonfiction, how-tos. Books, columns, articles–about all kinds of subjects, but especially about sex and relationships.

I also spent a fair amount of time in front of TV cameras. My path to semi-fame on television started with a wisecrack. At an audition for a British sex makeover show, a producer asked what I thought about women faking orgasms, and I shot back, “That’s nothing—men fake whole relationships.”

It got me the co-hosting gig on The Sex Inspectors, a sex advice show that became an international hit. Even HBO picked it up.

One moment, I was touring the world, appearing on The Today Show, writing books, and living the kind of life that would make a former version of myself proud.

Then, fast forward. I was no longer auditioning for TV shows. I was auditioning my misery–trying to convince a psychiatrist—and my insurance company—that my depression was bad enough to qualify for ketamine treatment.

The path between these two points wasn’t a straight line. After my TV career ended, I struggled with increasing isolation. I had always cycled through depressive episodes but two things seemed to have made it permanent. First, were years of chronic financial anxiety that ended in me filing for bankruptcy.

But it was a profound family crisis that pushed me over the edge—a crisis that ended in a betrayal so devastating I just couldn’t come back from it.

I cycled through three different medications, each with devastating side effects. The first killed my sex drive, the second caused significant weight gain, and the third amped up my anxiety to unbearable levels. With all three I experienced an emotional deadness that made everything feel flat and distant.

The drugs didn’t work. I was barely functioning, using Adderall to work, Clonopin to sleep, and alcohol to fill the gaps.

Then Matthew Perry died.

▶️ Watch: How ketamine ended my depression in six weeks—and why I’m now helping others find their way through it:

Beneath the tabloid frenzy over his ketamine overdose, one detail stopped me cold—Matthew Perry had been undergoing therapy with ketamine in a medically supervised clinic to treat depression.

Wait. What?

I’d taken ketamine in my party days, watched friends vanish into K-holes, seen the way it warped time and reality. How the hell was this the same drug now being used as an antidepressant?

![]()

While the world fixated on the scandal of Perry’s death—the shady doctors accused of selling him ketamine illegally, the now-infamous “Ketamine Queen” keeping the supply flowing—I started digging. And what I found floored me.

Ketamine wasn’t some fringe experiment. It had an impressive track record of successfully treating depression–certainly more than SSRIs had. A strange feeling bubbled up inside me–hope.

I was broke (remember, I filed for bankruptcy) but I still had insurance, so I figured maybe, just maybe, ketamine treatment was within reach.

Then came the first gut punch: insurance wouldn’t cover the treatments I wanted–IV or injections. The only thing they’d pay for was Spravato, the esketamine nasal spray.

Then came the knockout blow: even with insurance, a full course of Spravato would cost me $8,000 out-of-pocket.

I didn’t have $8,000. So I gave up. Ketamine therapy wasn’t just out of reach for the recently bankrupted—it was out of reach for most people. Who has thousands of dollars lying around for medical treatment insurance won’t cover? This wasn’t some luxury wellness trend; it was a proven treatment for severe depression.

As I slid deeper into depression, a friend threw me a lifeline: Johnson & Johnson, the makers of Spravato, he said, offered massive subsidies—ones that were shockingly easy to qualify for. And I did.

I remember my first ketamine session: I was in the clinic treatment room with a video camera pointed at me and a panic button at my side, wondering whether I was in therapy or a hostage situation! Turns out they’re just standard safety precautions.

I thought I was prepared.

I’d done my homework—read the medical websites, pored over clinical studies, studied the manufacturer’s official information. They told me what to expect, laid out the side effects, the mechanisms, the science.

But they left out one thing.

It was almost as if they didn’t want me to know.

And then, I experienced them.

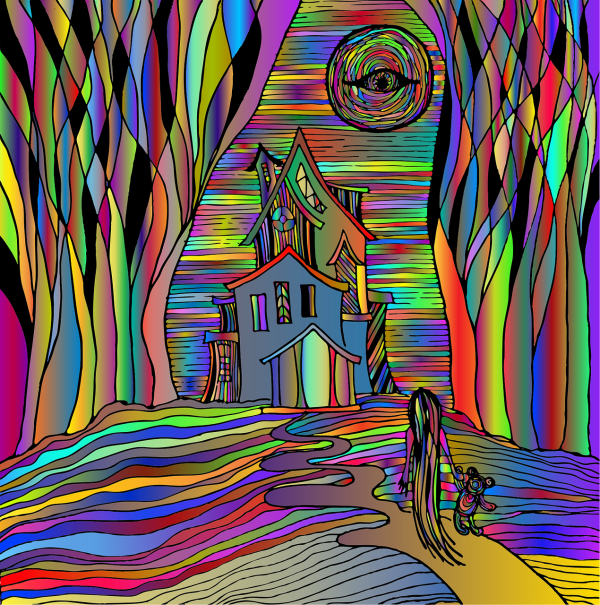

Profound. Vivid. Intense.

Psychedelic visions.

Nobody warned me about the visions. And I had plenty of them. Some were unsettling—horrifying, even. But here’s the weird thing: I never experienced terror. I seemed to be in three states of consciousness at once.

Take one of my most terrifying psychedelic visions as an example—I saw myself as a kind of serial killer, burying myself alive in a coffin with an air pipe, ensuring I would suffer longer.

One part of me calmly orchestrated a nightmare—methodically burying myself alive—while another part was trapped in the coffin, in full-blown panic, desperate to get out.

But then there was a third aspect, an observer, detached and serene, watching the entire scene unfold with a strange, unshakable calm. It was as if I was standing behind a thick pane of glass, able to see and understand the terror but somehow shielded from fully feeling it.

I was both the victim and the villain, and yet also something beyond both—a witness with a sense of equanimity that felt completely at odds with the horror unfolding before me. It didn’t make sense. How could I be in the thick of such dread, yet remain untouched by it?

This turned out to be a common feature of ketamine-fueled psychedelic visions—the simultaneous presence of intense emotional states alongside a profound sense of detachment. Ketamine disrupted the brain’s normal processing pathways, creating a unique dissociative state where multiple layers of consciousness coexisted.

This is why it was possible to feel like both the perpetrator and the victim while also stepping back as a detached observer. That third perspective—the one watching with equanimity—acted as a kind of psychological buffer, allowing me to confront deeply unsettling emotions without being overwhelmed by them.

Ketamine’s dissociative effects essentially split my awareness into compartments, making it possible to engage with fear, grief, or terror from a protected vantage point.

That “thick glass” sensation was my brain’s way of creating emotional distance, letting me explore difficult emotions without being consumed by them. It was like standing on an observation deck, looking down at something painful but staying grounded in a state of relative calm.

This compartmentalization was part of what made ketamine such a powerful tool for healing. It allowed access to buried emotional truths while keeping me anchored, letting me see and understand aspects of my psyche that might otherwise be too overwhelming to confront directly.

Instead of being swallowed by fear, I could observe it. Instead of drowning in grief, I could study it. And instead of being destroyed by my past, I could finally begin to make sense of it.

And that’s why these visions weren’t just bearable—they were instrumental. They unearthed things buried deep, brought emotions to the surface, and showed me parts of myself I might never have faced otherwise. Some were terrifying. Others were profound. Some felt like a direct line to something bigger than myself.

I credit these visions for my healing because they were a portal to parts of me that no conversation, no analysis, no traditional therapy could have ever reached.

My first psychedelic vision exemplified this:

I felt myself floating, weightless, drawn toward a giant martini glass. Then, I wasn’t just in the drink—I was the drink. And not just the drink. I was the glass holding it, the table beneath the glass, the ground beneath the table. I dissolved into it all, merging with the world in the only way that finally felt right—by no longer being in it.

I knew how absurd this was. A table that thinks? A martini with opinions? The ground itself, relieved that I no longer walked on it? The logic was impossible, but the feeling was real.

Then a thought broke through, slicing through the surreal haze like a knife. Why did I want to disappear so badly?

The weight of that question crushed me. I started to cry—deep, relentless sobs that shook my entire body. Each wave of grief crashed harder than the last, pulling me under, refusing to let go. My need for self-erasure was so absolute that I was willing to become anything—alcohol, glass, wood, earth—anything but me.

And that’s when I saw it. The truth I had never dared to name: I didn’t want to exist anymore.

With the help of a psychotherapist I could see these weren’t random images. They were metaphors, sent from the depths of my mind, forcing me to confront what I had spent a lifetime trying to bury. Take the vision about disappearing into the martini glass–it was essentially about my desire for self-erasure, about wanting to die.

Or was it?

I came to see it more as a metaphor for my early childhood. See, my father left and wiped us away like chalk on a blackboard. My mother legally changed my first name because she couldn’t bear that it was my father’s.

She banned us kids from speaking Spanish (our native tongue) because her new husband didn’t like it, and coerced us into being adopted by him even though my biological father was still alive. Everything about me was erased–my father, my name, my connection to my father’s big, warm South American family.

Even I got into the act—I tried bleaching my skin as a kid, wishing away the parts of me I had been taught shouldn’t exist.

If I hadn’t had that psychedelic vision, I might never have been able to process the theme of erasure that riddled my childhood. The experience of dissolving into the martini glass wasn’t just about wanting to disappear—it was about being made to disappear, over and over again.

Without that vision forcing me to sit with the feeling of vanishing, I might have continued avoiding the truth of what had happened to me. I might have looked at my childhood as painful but never quite named what made it so unbearable: the slow, deliberate dismantling of who I was.

The vision gave shape to something I had never been able to fully grasp. It wasn’t just grief over losing my father; it was the totality of being erased—my name, my language, my identity. It was the unspoken message that who I was wasn’t worth keeping. That I had to become someone else to be acceptable.

Had I not seen myself dissolve so completely in that vision, I might not have recognized just how deep that wound ran. And without seeing it, how could I ever hope to heal it?

One day, I walked into the clinic and caught my reflection. I was clean-shaven. Dressed well. I had woken up early—early!—to work out before my session. That wasn’t me. That was some other person, someone who had been creeping into my skin without me noticing. And I realized that ketamine hadn’t just been breaking me apart; it had been rewiring me without my being aware of it.

The strangest thing about healing is how quiet it is. It doesn’t announce itself. There is no grand epiphany, no movie-montage moment where everything falls into place. It happens like a soft edit, a detail you almost miss. You realize you’re drinking less. You answer the phone instead of letting it go to voicemail. You say yes to an invitation without dreading it for days. It is subtle. Unassuming. And then one day, your psychiatrist looks at you and says, “Technically, you’re in remission.” And you burst into tears because you never thought you’d hear those words.

I don’t believe ketamine is a miracle drug. I don’t believe in miracles at all. But I believe in this: When you’ve lived in the dark for long enough, sometimes all it takes is a single match to remind you what light looks like.

For me, ketamine was that match.

Ketamine ended my depression in 6 weeks.

I want the same for you.

Drawing from my own journey, I’m dedicated to raising awareness of this life-saving treatment, inspiring others to consider it, guiding them through our soul-crushing healthcare system to get the care they need, and optimizing their experience to maximize the chances for complete remission. Read more about mission here.

Owner/Publisher: Michael Alvear • ketaminetherapyfordepression.org • Contact • Location: Atlanta, GA • Editorial standards and update/corrections process.