Can Ketamine Help You Stop Drinking Alcohol?

What 16 Studies Actually Show

Key Findings →

Browse Database →

See Conditions →

See Mechanisms →

Protocol Details →

Knowledge Gaps →

By Michael Alvear, Health Author & Independent Researcher

My research is published on these scholarly platforms:

Last Updated:

I was three weeks into Spravato treatment for my depression when I noticed something strange: I hadn’t had a drink since the treatment started. My desire to drink completely disappeared.

This made no sense as I was a heavy drinker, polishing off a bottle of wine a night.

Yet there I was, with zero interest in alcohol. None. When the craving eventually came back, I was drinking maybe a quarter of what I used to.

Ten months later, I went to a ketamine therapy retreat. Same thing happened. The pull toward drinking, POOF! disappeared again. This time I couldn’t dismiss it as coincidence.

Then I learned I wasn’t alone. Ketamine subreddits are filled with people talking about an unexplained loss in desire for alcohol. Heck, scientists know this phenomenon goes back 1960s when surgery patients given ketamine as an anesthetic reported the same experience: they went home and suddenly didn’t want to drink.

I’m a researcher. When something this consistent shows up in my own life and across decades of reports from others, I need to know: Is this real, or are we all experiencing some version of placebo?

So I dug into every study I could find. Sixteen studies total. Some are gold-standard randomized controlled trials published in the American Journal of Psychiatry and Nature Communications. Others are small pilots with 5 participants that can’t prove anything.

Here’s what the evidence actually shows: Ketamine demonstrates promise — not proof — for reducing alcohol consumption and cravings.

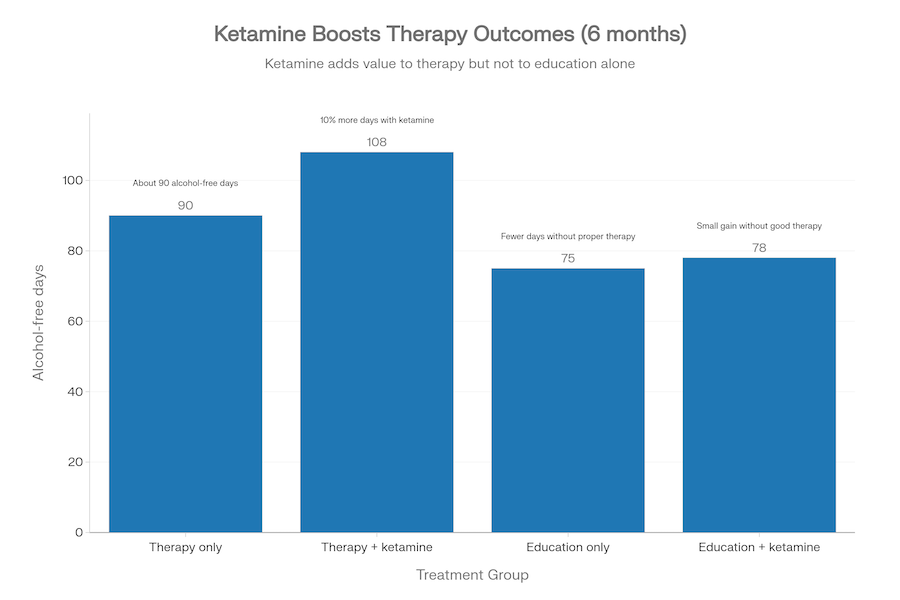

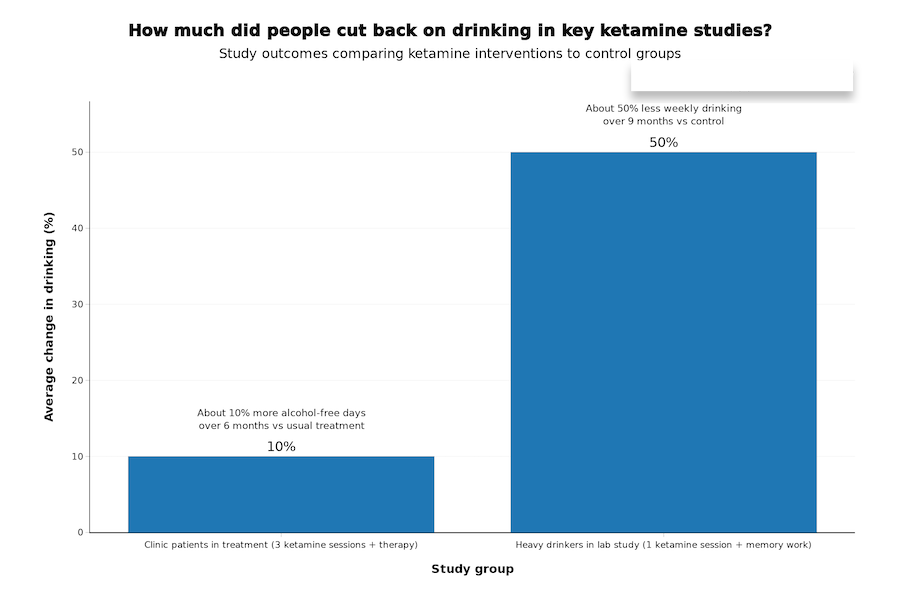

In the best-designed studies, people who received ketamine (usually combined with therapy) had about 10% more abstinent days over six months compared to placebo. One study showed a 50% reduction in weekly drinking when ketamine was timed with memory reactivation techniques. These aren’t small effects.

But here’s the part that matters just as much: another well-designed trial found no alcohol benefit at all, even though ketamine improved depression in the same patients.

The results are mixed, the evidence is encouraging but the studies are small — the largest had 96 people. We don’t know who responds and who doesn’t. We don’t know the optimal dose, how many sessions, or how long effects last.

Some studies combined ketamine with intensive psychotherapy; others didn’t. Context seems to matter, but we don’t understand how.

But here’s what I also know: If you’re in pain about your drinking, or watching someone you love struggle with it, you deserve to see the actual evidence — both the promising parts and the limitations — so you can make an informed decision. You shouldn’t have to rely on Reddit threads or sensationalized media stories. You need the real studies, explained clearly.

That’s what this page does.

Below, I’ve organized all 16 studies by scientific confidence. The high-tier evidence — randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews — appears first. These are the studies scientists trust most.

Medium-tier evidence includes pilots and qualitative research that suggest possibilities but can’t prove them. The low-tier study is included for completeness but shouldn’t guide your decisions.

The evidence shows:

- What researchers actually found (not what they hoped to find)

- Why the studies matter in the bigger picture

- The limitations that prevent us from calling the evidence “proof”

You’ll see exactly where the evidence is strong, where it’s weak, and where we simply don’t know yet. Because the truth — the complicated, incomplete truth — is more useful than false certainty.

The pattern I, and many others, experienced is real enough that scientists are studying it. But we’re still in the “promising signal” phase, not the “proven treatment” phase. Let’s find out more.

What 16 Studies Reveal About Ketamine’s Effectiveness in Reducing Or Eliminating Problem Drinking

Based on the 16 studies you’ll see in the next section below, this is where we stand today:

Does it work? The “Signal” in the Data

The data shows a consistent, positive signal that ketamine reduces both the urge to drink (cravings) and the frequency of drinking.

- Abstinence Rates: In high-quality trials (Grabski 2022, Dakwar 2020), participants receiving ketamine consistently had more alcohol-free days than those who didn’t.

- The “Krupitsky” Benchmarks: Older but large-scale studies (Krupitsky 1997) showed a dramatic gap: 65.8% abstinence for the ketamine group vs. 24% for standard care at one year. While modern standards for “randomization” are stricter, the sheer size of that gap is what first fascinated the scientific community.

The “Noise Reduction” Effect

Remember that “100% drop in desire” I and others have experienced (anecdotally)? This is reflected in the literature as Craving Reduction.

- Biological Reset: Studies like Das (2019) are particularly interesting here. They found that ketamine can “interfere” with the brain’s reward association with alcohol. This is likely what I and others felt—the brain’s automatic “need” for alcohol was temporarily disconnected.

- A Window For Change: Researchers are beginning to view ketamine as a tool that provides a “biological window” of sobriety. The “noise” goes away, giving the person time to build new habits before it potentially returns.

Why is More Research Needed If There Are So Many Promising Signals?

“Promising” means “this deserves more investigation” — not “this definitely works.” Here’s why more research is needed:

- Small samples = unreliable results. The largest study had 96 people. You can’t base treatment guidelines on 96 people. Flukes happen in small samples.

- Mixed results = we don’t understand it yet. Some studies show benefit, others don’t. That tells us it works for some people in some circumstances, but we don’t know who or when.

- No standardized protocol. Studies used different doses, different numbers of sessions, different therapy types. We don’t know what actually works best.

- Short follow-ups. Most studies tracked people for weeks or months, not years. Do effects last? We don’t know.

- Mechanism is unclear. We don’t understand why ketamine might reduce drinking, which makes it hard to optimize treatment or predict who will respond.

Bottom line: Promising evidence means “this signal is strong enough to justify spending millions on larger, longer trials.” It doesn’t mean “start prescribing this tomorrow.”

A Note of Caution

Hope moves faster than data.

When someone is scared about their drinking—or exhausted by it—anything that sounds like a new lever can start to feel urgent. And urgency has a habit of sanding off nuance. That’s where distortion happens, usually without anyone being malicious.

“Promising” gets translated into “proven.” “Could help some” becomes “will help me.” A measured finding turns into a headline.

And once that happens, it’s easy to start asking the wrong kind of questions.

Most people ask: “Will ketamine make me stop drinking?”

That question invites fantasy.

The better question is sharper: “Can ketamine create a window where therapy and behavior change actually stick?”

Because the best trials don’t make ketamine look like a magic eraser. They show something more specific: in studies where ketamine was combined with structured therapy—particularly mindfulness-based relapse prevention or motivational enhancement—people had about 10% more abstinent days over six months compared to placebo. When ketamine was given alone, or with minimal therapy, results were inconsistent.

The leading hypothesis is that ketamine temporarily disrupts how the brain consolidates reward-based learning. In one trial, when people reactivated alcohol-related memories and then received ketamine, their drinking dropped by roughly 50% and stayed lower for months. The interpretation: ketamine may weaken the automatic “cue → craving → drink” circuit, but only during a specific window after those memories are activated.

Not a cure. More like traction.

If you’ve ever tried to change a habit on sheer willpower, you know what it feels like: you push, you slip, you push again. Ketamine, in the best-case interpretation of the evidence, may create a neurobiological window—lasting days to weeks—where cravings are quieter and new patterns are easier to encode. But that window closes. And what you do during it—therapy, new routines, different environments—appears to determine whether changes last.

The Complete Evidence on Ketamine for Drinking: Every Study, Ranked by Strength

Most articles about ketamine’s effect on drinking alcohol show you the exciting studies and ignore the rest. I’m showing you everything — the promising trials, the mixed results, and the one that found no benefit at all. Each study is ranked by how much scientists trust it: gold-standard randomized trials at the top, small pilots at the bottom. This is how you spot the difference between hype and real evidence.

Complete Evidence Database

16 studies sorted by scientific confidence — from gold-standard trials to preliminary research

HIGH Confidence

MEDIUM Confidence

LOW Confidence

10

HIGH Confidence Evidence

Gold-standard RCTs and systematic reviews — the strongest evidence available

5

MEDIUM Confidence Evidence

Pilots, qualitative studies, and narrative reviews — suggestive but not conclusive

1

LOW Confidence Evidence

Very small, uncontrolled studies — hypothesis-generating only

Understanding Study Quality Matters

This tiered database shows you exactly which studies scientists trust most and why. Not all evidence is created equal — knowing the difference protects you from misleading claims.

The Ketamine-Alcohol Evidence Summary for Clinicians

Want to discuss ketamine with your doctor or therapist? Download this structured summary of 15 clinical trials. It organizes the evidence by scientific confidence, dosing protocols, and patient outcomes, providing a data-backed framework for your next medical consultation.

- All 15 clinical trials ranked by evidence quality

- Dosing protocols used in each study

- Patient outcomes and effect sizes

- Limitations and confidence ratings

- Direct citations to original research

📥 Download the Clinical Summary

CSV format • Works with Excel, Google Sheets, or any spreadsheet software

When Does Ketamine Actually Help with Drinking Problems? What the Studies Show

No study can promise an individual outcome. But the pattern across the stronger evidence points to practical conditions that matter.

Ketamine seems more likely to help when:

- The person is motivated to change and willing to engage in serious therapy, not just receive a drug and hope.

- Ketamine sessions are tied directly to relapse-prevention skills: identifying triggers, building alternative responses, practicing coping strategies, and designing a plan for high-risk moments.

- The program is structured: clear dosing schedule, clear therapeutic framework, clear outcome tracking.

Ketamine seems less likely to help when:

- It’s used as a standalone “experience” without skills training, integration, or follow-up.

- There’s no measurement: no baseline drinking pattern, no consistent tracking, no definition of success.

- The person expects ketamine to override a daily environment that keeps feeding the behavior—stress, isolation, availability, routines, social pressure.

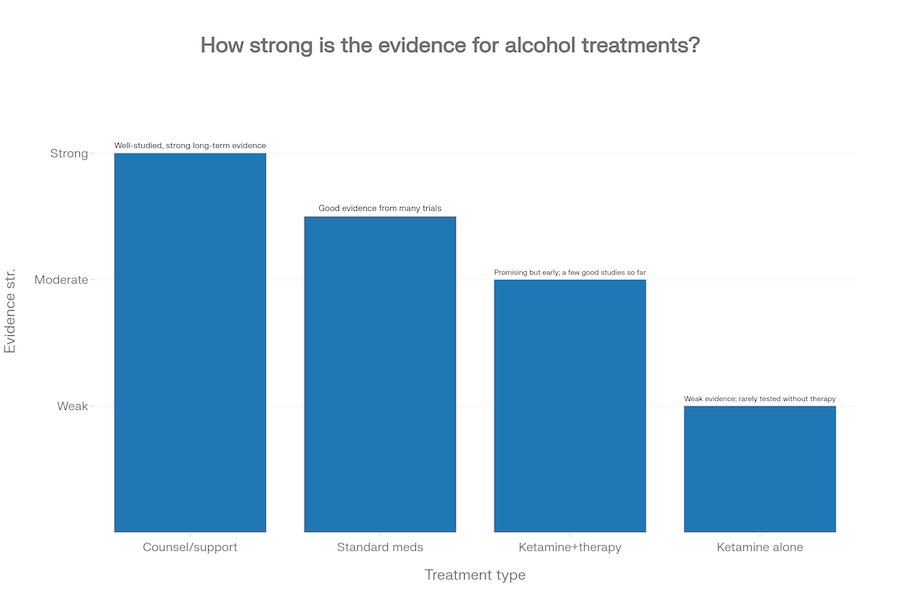

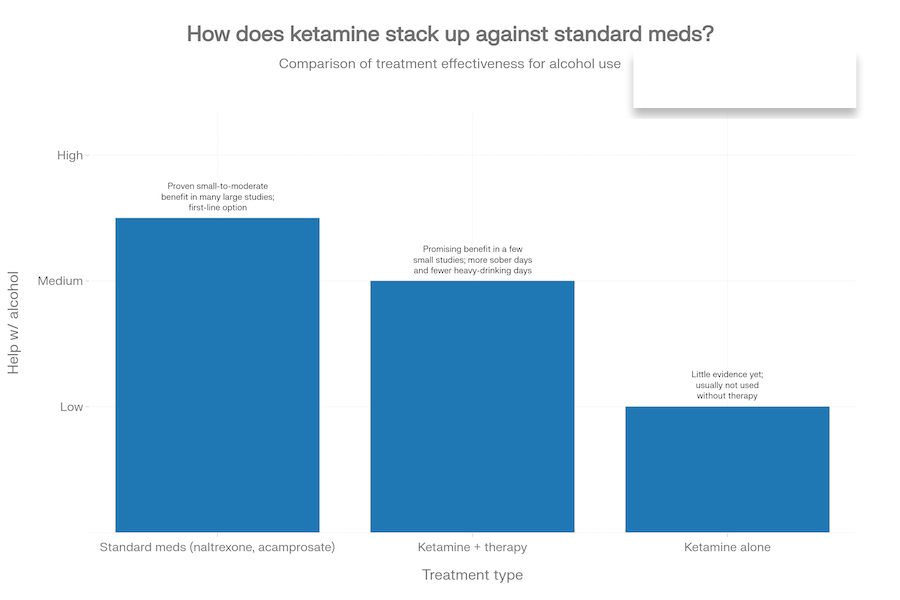

If you’re deciding what to try first, the hierarchy still matters: well-studied approaches (evidence-based therapy, mutual-support models, and approved medications like naltrexone or acamprosate when appropriate) currently rest on a deeper evidence base for alcohol outcomes than ketamine does.

That doesn’t make ketamine irrelevant. It puts it in a more realistic category: potentially useful as an add-on or a second-line option, particularly when standard approaches haven’t been enough.

Should You Try Ketamine for Your Drinking Problems?

From a purely evidence-based perspective, the answer is: “maybe—if the program is serious”.

Here’s what “serious” means based on the studies:

The evidence supports ketamine when it’s:

- Paired with structured psychotherapy—particularly motivational enhancement therapy or mindfulness-based relapse prevention. Studies where ketamine was given alone or with minimal therapy showed inconsistent results.

- Delivered as multiple sessions (3+ infusions), not a single dose

- Following research protocols: IV infusions at sub-anesthetic doses (0.5-0.8 mg/kg), spaced 1-3 weeks apart

- Part of a comprehensive program with medical screening and aftercare planning

It may be worth exploring if:

- Standard treatments haven’t helped enough and the drinking pattern is dangerous or worsening

- The ketamine work is integrated with structured therapy aimed directly at drinking behavior

- There is a plan for aftercare and relapse prevention, not just sessions

- You understand this creates a window, not a permanent fix

It may not be worth it if:

- You’re hoping for a reset button—the evidence shows ketamine shifts patterns, doesn’t erase them

- The cost crowds out proven support you could sustain over time (therapy, mutual support groups, ongoing medical care)

- There are medical or psychiatric risk factors that make ketamine a poor fit—something only a qualified clinician can evaluate

- The program can’t clearly explain why their approach matches what worked in clinical trials

The studies show ketamine creates a neurobiological window where change is easier. What matters is whether there’s a real plan for that window—structured therapy during treatment and sustained support after.

Quiz: Does Your Profile Match Successful Ketamine Trial Participants?

The abstract question “should I try ketamine?” becomes clearer when you compare your specific situation to the people who were actually enrolled in these trials.

The quiz below walks through the same screening criteria researchers used in the Grabski, Dakwar, and Das studies—drinking patterns, treatment history, medical factors, and motivation for change.

It gives you a detailed breakdown of whether your profile matches trial participants who saw benefit, whether there are medical concerns to address first, or whether other approaches make more sense right now.

Important: This isn’t a diagnostic tool or medical clearance. It’s a framework to help you have a more informed conversation with a clinician—or to recognize when ketamine isn’t the right fit.

Could Ketamine-Assisted Therapy Help My Alcohol Problem?

This assessment compares your situation to participants in major clinical trials (Das 2019, Dakwar 2020, Grabski 2022) to determine whether ketamine + therapy might be appropriate to discuss with a clinician.

⚠️ This is educational only—not medical advice or treatment clearance.

Your Situation Requires Immediate Medical Attention—Not Experimental Ketamine

- Dangerous withdrawal risk: If you've had seizures, hallucinations, or severe physical symptoms when stopping alcohol, you need medically supervised detox before any other intervention. Ketamine trials specifically excluded people with active severe withdrawal.

- Crisis-level urgency: Thoughts of self-harm or feeling unsafe require immediate crisis intervention—call 988 (Suicide & Crisis Lifeline) or go to your nearest emergency room. Ketamine research is for stabilized patients, not acute crises.

If in crisis: Call 988 (U.S. Suicide & Crisis Lifeline), text "HELLO" to 741741 (Crisis Text Line), or go directly to an emergency room. These are free, confidential, 24/7 resources.

For alcohol-related emergencies: SAMHSA National Helpline is 1-800-662-HELP (4357)—free, confidential, 24/7 treatment referral and information service.

For severe withdrawal: Contact your doctor immediately or go to an ER. Medical detox programs can safely manage withdrawal with medications like benzodiazepines, thiamine, and close monitoring.

Once withdrawal risks are addressed and you have a safety plan in place, then you could revisit experimental options like ketamine with a specialist. The treatment pathway typically looks like:

- Medical stabilization and withdrawal management

- First-line treatments (naltrexone, acamprosate, therapy)

- If those don't work adequately, explore experimental options under close supervision

Important: None of the ketamine trials (Das 2019, Dakwar 2020, Grabski 2022) enrolled people with active dangerous withdrawal or current suicidality. Your immediate priority is safety and medical stabilization—ketamine can potentially be discussed months from now with the right medical team.

Ketamine Probably Isn't the Right First Step for You

- Your drinking pattern may not match trial criteria: If you're drinking less than weekly or rarely binge drinking, you're outside the "hazardous" or "dependent" range that clinical trials targeted. The Grabski 2022 and Das 2019 studies enrolled people drinking 5+ days per week or consuming 40+ standard drinks weekly.

- You haven't tried proven treatments yet: All major ketamine trials enrolled people after they'd tried standard medications (naltrexone, acamprosate) or structured therapy. These first-line treatments should come first because they have:

- FDA approval and extensive safety data

- Decades of research with thousands of participants

- Known cost, accessibility, and insurance coverage

- Clear protocols for medical management

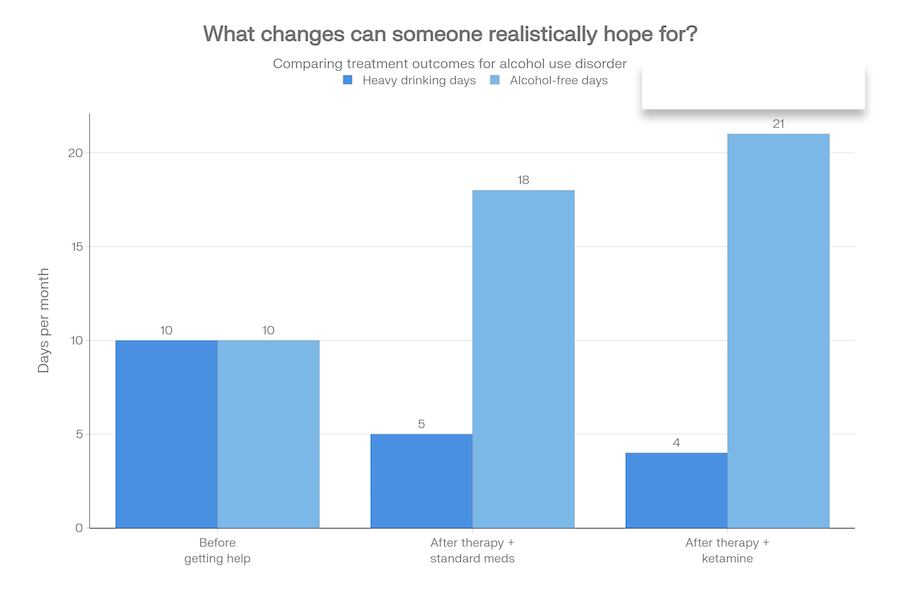

- Unrealistic expectations: If you're hoping ketamine will "magically erase" the problem, that's not supported by evidence. The Grabski trial showed 10% more alcohol-free days (~18 extra days out of 180)—meaningful, but modest. This is a tool to enhance therapy, not a standalone cure.

1. Start with FDA-approved medications:

- Naltrexone: Blocks opioid receptors, reduces the "buzz" from alcohol and decreases heavy drinking days. For every 12 people treated (vs placebo), 1 additional person avoids relapse.

- Acamprosate: Modulates glutamate, reduces cravings and supports abstinence. Similar NNT of 12 for maintaining abstinence.

- Disulfiram: Makes you sick if you drink—works through aversion, best for highly motivated people with supervision.

2. Engage in evidence-based therapy:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Teaches you to identify triggers, challenge thinking traps, and develop coping strategies.

- Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET): Helps resolve ambivalence and build internal motivation to change.

- Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP): The same therapy used in the Grabski ketamine trial—effective on its own.

3. Consider intensive programs if needed: Outpatient programs, partial hospitalization, or residential treatment provide structure and comprehensive support.

Absolutely. If you try naltrexone + therapy for 3–6 months and don't get adequate results, ketamine becomes a more reasonable option to discuss. At that point:

- You'll have demonstrated treatment resistance (a key inclusion criterion in trials)

- You'll understand what therapy involves and be better prepared for the ketamine + therapy protocol

- More research data will be available (the MORE-KARE trial with 280 participants reports results in 2026–2027)

- You'll have ruled out simpler, safer options first

Bottom line: This isn't a permanent "no"—it's a sequencing recommendation based on how researchers structure care. Try proven treatments first, document what does and doesn't work, then revisit experimental options with your treatment team if needed.

Ketamine Might Be Worth Discussing—But Only After Careful Medical Evaluation

Your responses suggest you share some characteristics with people who participated in ketamine + therapy trials:

- Hazardous or dependent drinking: You're in the severity range that trials targeted

- Some treatment history: You've tried at least one or two evidence-based approaches

- Openness to therapy: You understand ketamine requires real therapeutic work, not just infusions

However, you also indicated possible medical or psychiatric risks that require thorough evaluation before moving forward. This is crucial because:

Cardiovascular concerns: Ketamine temporarily increases blood pressure and heart rate during infusions. Uncontrolled hypertension (systolic >160 mmHg or diastolic >100 mmHg) was an exclusion criterion in the Grabski trial. You need:

- Blood pressure monitoring and optimization

- EKG if you have any cardiac history

- Cardiologist clearance if you have known heart disease

Psychiatric red flags: History of psychosis, mania, or active hallucinations typically excludes people from ketamine treatment because:

- Ketamine causes dissociation and can be destabilizing in severe mental illness

- NMDA antagonists may worsen psychotic symptoms

- You need a psychiatrist to assess risk vs benefit

Bladder issues: Chronic ketamine use (especially in recreational contexts) can cause ketamine-induced cystitis—painful, irreversible bladder damage. If you already have bladder disease, repeated ketamine could worsen it.

Unknown conditions: If you answered "not sure" about contraindications, you need comprehensive medical screening before any ketamine discussion.

Copy or screenshot these questions to structure a productive conversation with an addiction specialist or psychiatrist:

- "Given my drinking pattern, treatment history, and medical conditions, could ketamine-assisted therapy be appropriate for me at some point?"

- "What medical tests or evaluations would I need before considering ketamine?" (e.g., blood pressure monitoring, EKG, psychiatric assessment, urinalysis)

- "Are there standard treatments I should try first or continue while exploring ketamine?"

- "If ketamine is an option, what protocol would you recommend?" (single infusion + motivational therapy like Dakwar 2020, or three infusions + mindfulness therapy like Grabski 2022)

- "What are the specific risks for someone with my medical history, and how would those be monitored?"

- "What would a realistic timeline look like—stabilizing other conditions first, then potentially ketamine in X months?"

Many people in the early ketamine trials had complex histories—comorbid depression, anxiety, prior treatment failures. The key difference is they were medically cleared and carefully monitored. Your path might look like:

- Phase 1 (0–3 months): Complete medical workup, optimize blood pressure or other conditions, stabilize psychiatric medications if applicable.

- Phase 2 (3–6 months): Continue or start first-line treatments (naltrexone, therapy) while medical team determines ketamine safety.

- Phase 3 (6+ months): If cleared medically and still struggling despite standard treatments, initiate ketamine + therapy protocol with close monitoring.

Key takeaway: You're not categorically excluded, but you need a clinician who can review your full medical picture, order appropriate tests, and make an informed decision about timing and safety. Don't rush into ketamine clinics without this evaluation—responsible providers will require it anyway.

Your Profile Matches Clinical Trial Participants—Ketamine + Therapy Is Worth Discussing

- You have hazardous or dependent drinking: This matches the severity level of participants in the Grabski 2022 (UK trial, 96 participants), Dakwar 2020 (Columbia University, 40 participants), and Das 2019 (UCL, 90 participants) studies.

- You've tried evidence-based treatments: All major trials required participants to have attempted standard approaches first—you've done that and are still struggling, which is the exact treatment gap ketamine research addresses.

- No obvious medical red flags: You don't report uncontrolled hypertension, psychosis, severe heart disease, or other exclusion criteria used in trials.

- Realistic expectations: You understand ketamine is a tool to enhance therapy and create a "window" for change—not a magic cure. This mindset aligns with how it's used in research.

- Willing to do therapy: The evidence is clear: ketamine alone doesn't work. You're prepared for the structured therapy component (mindfulness-based relapse prevention, motivational enhancement, or memory reconsolidation work).

Primary outcomes from the Grabski 2022 trial (largest and most rigorous):

- 10% more alcohol-free days at 6 months: This translates to roughly 18 extra sober days out of 180 compared to therapy alone. Small-to-medium effect size, but clinically meaningful.

- Biggest benefit with ketamine + real therapy: People who got ketamine plus mindfulness-based relapse prevention had 16% more abstinent days at 3 months vs those who got placebo plus basic education.

- Ketamine without therapy showed minimal benefit: Proves the drug alone isn't enough—the therapeutic work is essential.

Outcomes from Dakwar 2020 trial (single ketamine + motivational therapy):

- 75% abstinence rate at 6 months: 6 out of 8 people in ketamine group stayed completely sober vs 3 out of 11 in control group (NNT=4, which is large effect).

- Delayed time to relapse: Ketamine group went significantly longer before first heavy drinking day.

- Mystical experiences mattered: People who had profound, meaningful experiences during the infusion (feelings of unity, transcendence, awe) had better outcomes—suggesting the subjective experience is therapeutically important, not just the chemical effects.

Das 2019 memory reconsolidation trial: People who got ketamine after alcohol memory reactivation reduced weekly drinking by approximately 50% for 9 months (from ~672g/week to ~328g/week).

- 3 weekly ketamine infusions (0.8 mg/kg IV over 40 minutes)

- 7 therapy sessions (1.5 hours each) teaching mindfulness, urge surfing, trigger management, values work

- Best for: People who respond well to mindfulness/meditation and want comprehensive skill-building

- Evidence level: Strongest (96-person RCT with objective alcohol monitoring via ankle bracelets)

- Single ketamine session after activating vivid drinking memories

- "Prediction error" technique: expect the drink but don't get it, then receive ketamine to "rewrite" the reward memory

- Best for: People with strong, specific drinking cues tied to particular drinks/places/rituals

- Evidence level: Moderate (90-person RCT, but lab-based study with hazardous drinkers, not seeking treatment)

- Single ketamine infusion (0.71 mg/kg IV) on a designated "quit day"

- 6 motivational counseling sessions over 5 weeks to build commitment and resolve ambivalence

- Best for: People who are ambivalent about quitting but want a clear "fresh start" moment

- Evidence level: Moderate (40-person pilot trial, short 21-day follow-up)

Bring this assessment plus the following talking points to an addiction psychiatrist, addiction medicine specialist, or your primary care doctor with addiction expertise:

- "I've tried [naltrexone/acamprosate/therapy] and while it helped somewhat, I'm still struggling with [X drinking days per week / X drinks per day / relapses every X weeks]."

- "I've read about ketamine-assisted therapy for alcohol use disorder. The Grabski 2022 UK trial and Dakwar 2020 Columbia trial both showed meaningful benefits when combined with structured therapy."

- "I understand this is experimental and not FDA-approved for alcohol problems. I'm not looking for a magic cure—I'm willing to do real therapy work (mindfulness-based relapse prevention or motivational counseling)."

- "Based on my medical history, do you think I'm a candidate? If so, what protocol would you recommend? If not, what else should I try?"

- "Are there any medical tests or evaluations I'd need first? And would this be done alongside continuing naltrexone [or other medication], or as a replacement?"

Before infusion:

- Medical screening (blood pressure, heart rate, psychiatric evaluation)

- Therapy session to set intentions and prepare

- Consent process explaining risks and unknowns

During infusion (40–52 minutes):

- IV placed in your arm, ketamine administered slowly

- Continuous monitoring of vital signs (BP, heart rate, oxygen)

- You remain awake but may feel dissociation (floating, detached, dreamlike)

- Some people have visual changes, time distortion, or profound/spiritual experiences

- Effects are temporary and resolve within 1–2 hours after infusion ends

After infusion:

- 2–3 hours of observation in clinic before discharge

- Someone must drive you home (you cannot drive same-day)

- Therapy session within 24–48 hours to integrate the experience

- Ongoing therapy sessions and relapse prevention work

Common side effects (Grabski 2022):

- Temporary high blood pressure (resolves within hours)

- Fast heartbeat during infusion

- Feelings of dissociation or euphoria

- Low mood the next day (transient)

- 20 out of 96 participants had side effects; most were mild and didn't require intervention

- Still experimental: Not FDA-approved for alcohol use disorder. Long-term safety beyond 9–12 months is unknown.

- The MORE-KARE trial (280 participants) won't report results until 2026–2027: This will be the most definitive evidence. If you can wait, consider enrolling in that trial or waiting for results.

- Insurance typically doesn't cover this: Expect to pay out-of-pocket ($400–$800 per infusion) unless you find a research program.

- Not a cure: Even in best-case scenarios (Dakwar trial), people still needed ongoing support and had to actively work on recovery.

- Unknown long-term effects: No data on safety or efficacy beyond 1 year. Questions remain about repeat dosing, bladder toxicity risk, cognitive effects, and abuse potential.

Final thought: Your situation makes you a reasonable candidate to discuss ketamine-assisted therapy with a qualified clinician. This doesn't mean you should rush into it—it means you're in the zone where the risk/benefit calculation is worth having a serious conversation about. Bring this assessment, ask the hard questions, demand evidence-based answers, and make an informed decision with your treatment team.

Medical Disclaimer: This self-assessment is for educational purposes only and does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment clearance. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider before making treatment decisions. Ketamine for alcohol use disorder is not FDA-approved and remains experimental. Evidence cited: Das et al. 2019 (Nature Communications), Dakwar et al. 2020 (American Journal of Psychiatry), Grabski et al. 2022 (American Journal of Psychiatry), MORE-KARE trial 2024 (NIHR).

Want to Use Ketamine to Stop Drinking? Do It the Way Successful Studies Did It.

If you want to use ketamine to reduce alcohol cravings and cut your intake, you cannot treat it like a “magic eraser”.

The best outcomes in clinical research occurred when the drug was used to open a brief “window of change” for specific, high-stakes therapy.

This 50-page workbook provides the exact session-by-session structures used in the Grabski (2022) and Dakwar (2020) trials. It includes worksheets for Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention and Memory Reconsolidation, allowing you to turn a temporary neuroplastic “window” into a permanent shift in drinking behavior.

Stop guessing at the protocol and start using the manual that is actually grounded in the data.

- Session-by-session structures from KARE and Dakwar trials

- Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention worksheets

- Memory Reconsolidation protocol and exercises

- Trigger identification and coping strategy builders

- Pre-session preparation and integration guides

- Evidence-based timing for maximum neuroplasticity

📥 Download the Treatment Blueprint

PDF format • 50 pages • Printable worksheets included

How Scientists Discovered Ketamine’s Effect on Alcohol Cravings: A Short History

Scientists didn’t set out to find an alcohol treatment when they discovered ketamine’s effects on drinking. They stumbled onto it.

In the 1960s and 70s, ketamine was being used as a surgical anesthetic—particularly in field hospitals during the Vietnam War. Doctors began noticing something odd: patients with alcohol use disorder who received ketamine for surgery would sometimes report that their cravings disappeared after they woke up. Not everyone. Not permanently. But often enough that it couldn’t be ignored.

For decades, these were just anecdotes in medical charts. But in the 1990s, Russian psychiatrist Evgeny Krupitsky began systematically testing whether the pattern was real. His team combined ketamine with intensive psychotherapy and reported dramatic reductions in relapse rates—65.8% abstinence at one year compared to 24% in control groups. The methods were rough by modern standards and the results were impossible to audit, but the signal was strong enough to get attention.

The breakthrough came when neuroscientists figured out why it might work. Ketamine blocks NMDA receptors—proteins in the brain that help encode memories and learning. Alcohol cravings aren’t just chemical dependency; they’re learned associations. See the bar, feel the urge. Smell whiskey, want a drink. These are memory circuits. Ketamine appears to temporarily disrupt how those circuits get reinforced, creating a window where the “cue → craving → drink” loop can be rewritten.

That hypothesis led to modern trials. Researchers in the UK, US, and elsewhere began testing ketamine not as a standalone drug, but as a tool to make therapy more effective—a way to quiet the automatic pull of cravings long enough for new patterns to take hold. That’s where the 16 studies in this article come from: a 30-year progression from surgical observation to controlled clinical trials testing whether ketamine, combined with structured therapy, can help people change their relationship with alcohol.

How Does Ketamine Work to Reduce Alcohol Cravings and Drinking?

Ketamine isn’t a daily “anti-craving pill.” It’s a short, intense intervention that may open a brief window where change is easier to learn—and easier to keep.

Ketamine might help with alcohol problems by loosening rigid patterns around reward, stress, and alcohol-linked learning, then giving you a short period where therapy and new habits can stick more easily. That “window” model shows up again and again in the best summaries of the evidence, including this alcohol-focused review of the human studies.

And here’s the part people miss: ketamine works very differently from standard alcohol medications. The strongest signals show up when it’s paired with structured psychological support—not when it’s treated as a standalone event.

Why ketamine might help with alcohol problems

1) “Unsticking” rigid brain circuits

Long-term heavy drinking reshapes circuits that handle stress, reward, and self-control. That’s why alcohol use disorder can feel like a tug-of-war you keep losing—even when your reasons to stop are real and urgent. A clinical overview of this broader landscape appears in this scoping review in Frontiers in Psychiatry.

Mechanistically, ketamine’s main action is tied to the glutamate system—central to learning and plasticity (the brain’s capacity to form new connections). That framing is summarized in this broader review of ketamine across substance use outcomes.

- At treatment-range doses, ketamine briefly blocks NMDA receptors and appears to trigger a surge of glutamate signaling in circuits involved in mood and decision-making, including prefrontal regions—covered in this systematic review in BJPsych Open.

- That cascade is associated with rapid changes in synaptic function and structure over hours to days—an interpretation discussed in the PMC review of ketamine and substance use disorders.

In depression research, this plasticity window is linked to short-term shifts in mood, motivation, and cognitive flexibility. In addiction research, the hypothesis is similar but more behavioral: the same window could make it easier to learn new patterns around alcohol and weaken old automatic responses, as discussed in the alcohol-focused systematic review.

Think of it as traction. Not salvation. Traction.

2) Softening alcohol-linked memories and cues

One of the most striking modern studies doesn’t frame ketamine as “anti-craving” at all. It frames it as a tool for changing how alcohol-related learning is stored. That idea is front-and-center in the 2019 Nature Communications trial in harmful drinkers.

- Participants first reactivated personal alcohol-related memories and cues, then received ketamine or control procedures—details are in the original Nature Communications paper.

- Over nine months, the ketamine-after-reactivation group showed a sustained reduction in weekly drinking compared with control groups, as reported in the same trial publication.

The proposed mechanism is “memory reconsolidation”: when a memory is reactivated, it becomes temporarily modifiable. Ketamine given during that window may blunt the emotional punch of alcohol-linked memories and reduce cue-driven pull—an interpretation discussed in this review of ketamine and substance use mechanisms.

In plain terms: the bar, the smell, the stress spiral, the “just one” moment—those cues may push less hard if the learning underneath them gets updated.

3) Creating a window where therapy works better

Here’s where the evidence gets more practical. Multiple trials and reviews emphasize that outcomes look strongest when ketamine is paired with therapy, not given alone—including the phase 2 trial indexed at PubMed (KARE trial publication).

- In the 2022 trial, ketamine combined with mindfulness-based relapse-prevention therapy produced the largest increase in alcohol-free days compared with placebo combinations, as detailed in the trial report.

- Reviews of ketamine in alcohol use disorder and withdrawal repeatedly highlight the same pattern: the most promising protocols pair ketamine with structured, skills-based psychological support before and after dosing, discussed in the Frontiers scoping review.

The working model is simple:

- Ketamine opens a short plasticity window—people may feel less stuck and more flexible, an idea reviewed in this PMC synthesis.

- Therapy delivered during and after that window helps people rehearse new coping strategies, rebuild routines, and plan for triggers while the brain is unusually ready to encode new patterns—summarized in the alcohol-focused review.

So ketamine isn’t “the treatment.” It’s more like a booster stage that can help good therapy land deeper—if the therapy is there.

Stop asking for a cure. Start asking about a window.

Most people ask: “Will ketamine make me stop drinking?”

That question invites fantasy.

A better question is sharper: “Can ketamine create a window where therapy and new habits actually stick?”

Because if ketamine helps, it may help most by changing the learning conditions—not by permanently removing your desire to drink.

So ask the questions that decide outcomes:

What happens after the session? What happens between sessions? What skills are being trained? What is the plan when stress hits? When the urge returns? When the old cues show up?

How Ketamine Compares To Standard Alcohol Medicines Like Naltrexone

Standard medications: steady, daily tools

Most established medications for alcohol use disorder are daily or regular tools with quieter, ongoing mechanisms—summarized in sources like the Frontiers review and the alcohol-focused systematic review.

- Naltrexone blocks opioid receptors involved in alcohol reward, which can reduce reinforcement and cravings (overview in Frontiers).

- Acamprosate aims to stabilize glutamatergic imbalance after long-term alcohol use, supporting abstinence after stopping (reviewed in the PMC systematic review).

- Disulfiram acts as a deterrent by making alcohol consumption physically unpleasant (discussed in Frontiers).

- Topiramate (off-label) may reduce heavy drinking by dampening reward/impulsivity pathways, though side effects can limit use (covered in the PMC review).

These medications generally require ongoing adherence and have been tested in larger, longer programs than ketamine has so far. Their average effects can be modest—but for the right person, they can still matter a lot (see Frontiers).

Ketamine: a short, intensive intervention plus therapy

By contrast, ketamine protocols for alcohol outcomes in research are usually episodic: one to three sub-anesthetic infusions over a short period, sometimes with boosters—illustrated in the KARE trial publication.

- Sessions have noticeable acute effects (including dissociation and altered perception) over roughly an hour, followed by hours to days of subtler shifts that may relate to mood, flexibility, and craving dynamics—reviewed in this PMC synthesis.

Key differences:

- Ketamine is episodic rather than daily.

- The most promising approaches embed ketamine inside structured therapy rather than treating dosing as the whole program (see KARE).

- The evidence base for ketamine in alcohol use disorder remains much smaller than for standard medications, and it is not broadly approved as an alcohol treatment in most countries (summarized in the alcohol-focused review).

In simple terms:

- Standard medications aim to reduce pull and risk over time.

- Ketamine aims to create a short, powerful shift that—when paired with therapy—may help people change learning and behavior faster than they otherwise could.

Combination approaches: ketamine plus therapy, ketamine plus meds

Ketamine plus psychotherapy

Nearly every serious discussion of ketamine for alcohol outcomes assumes psychotherapy is part of the package.

- The KARE program (three infusions plus mindfulness-based relapse prevention) is described at the University of Exeter’s KARE overview and published at PubMed.

- Earlier ketamine-assisted psychotherapy models also relied on intensive group and individual therapy, even if the methods were older and less standardized (see this PubMed record on early ketamine psychotherapy work).

This is why many experts frame ketamine as a therapy enhancer, not a standalone medication:

- Without therapy, any short-term shift may fade as habits and environments reassert themselves.

- With therapy, the plasticity window can be used to build routines, rehearse responses to triggers, and strengthen motivation—consistent with the interpretation in the KARE report.

Ketamine plus other medications

Some discussions propose combinations like ketamine plus naltrexone or other medications, but this is still early and largely unproven at scale (reviewed in Frontiers and discussed historically in this ScienceDirect review).

- A tiny pilot combined injectable naltrexone with weekly ketamine infusions and reported reductions in drinking and mood symptoms, but it included only five participants and had no control group, described in this Semantic Scholar record of the pilot report.

- Broader reviews suggest a theoretical logic—ketamine to disrupt entrenched learning, standard meds to reduce reinforcement if slips occur—but emphasize how preliminary this remains (see ScienceDirect).

Right now, there is no large, high-quality trial showing that “ketamine plus medication X” clearly beats “medication X plus good therapy.” Any such combination should be treated as experimental and pursued only with careful medical supervision.

What this means in practice if you’re considering ketamine

- Ketamine works differently from standard alcohol medications. It aims at a short window of plasticity and psychological change, rather than slow, steady receptor modulation—see the BJPsych Open systematic review.

- The most convincing results show up when ketamine is wrapped in structured therapy—consistent with mechanistic framing from Nature Communications (2019) and clinical outcome patterns in KARE (2022).

- For now, ketamine is best viewed as a potential amplifier of good therapy and behavior change—not a replacement for them, and certainly not a guaranteed cure (summarized in the alcohol-focused review).

If you’re worried you drink too much—or you’re watching someone you love get pulled under—standard treatments remain the first stop because the evidence base is deeper and longer-term (see this broader review of evidence across substances).

But if those approaches haven’t been enough, ketamine may be worth considering as a carefully chosen add-on inside a specialized program that is structured, outcomes-focused, and honest about what the science does and does not show.

Ketamine Dosing and Treatment Protocols Used in the Studies

How researchers actually delivered ketamine in clinical trials — doses, timing, and therapy approaches

Across the more credible studies, ketamine is used in relatively short courses, at sub-anesthetic doses, and almost always alongside some form of therapy. Benefits tend to show up within days to weeks, but durability varies—and we still don’t have a single “winning” protocol that clearly beats all others. That pattern is summarized in this alcohol-focused systematic review.

Doses and routes actually used in the research

In alcohol-focused trials and reviews, ketamine is not delivered at the very high doses seen in old anesthesia practice or some psychedelic-era protocols. It generally sits in the sub-anesthetic range.

- In the 2022 phase 2 trial published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, participants with alcohol use disorder received three IV infusions at 0.8 mg/kg over 40 minutes, as reported in the KARE trial publication (PubMed).

- In the 2019 Nature Communications study in harmful drinkers, researchers used a single IV infusion at a similar sub-anesthetic dose, timed immediately after alcohol-related memory reactivation, described in the Nature Communications trial.

- Earlier ketamine-assisted psychotherapy trials discussed in modern reviews include single IV dosing around 0.7 mg/kg, paired with motivational enhancement therapy, summarized in this BJPsych Open systematic review.

- Reviews covering alcohol use disorder and alcohol withdrawal describe a range of sub-anesthetic IV dosing (often around 0.35–0.8 mg/kg) and some IM injections in the 2–3 mg/kg range, particularly in older or non-Western protocols, as discussed in this Frontiers scoping review.

All of these are research doses delivered with monitoring. This is not a story about unsupervised use.

Single-dose vs multi-session schedules

The research splits into two broad design families: single-session and multi-session.

Single-session examples

- In the harmful drinkers randomized trial, one infusion given immediately after memory reactivation was associated with a large, sustained drop in weekly drinking over nine months versus controls, as reported in the Nature Communications paper.

- Some older ketamine-assisted psychotherapy models also relied on a single high-impact session embedded within a longer therapeutic course, described in this USF-hosted overview of ketamine psychedelic psychotherapy.

Multi-session examples

- The KARE trial used three ketamine infusions paired with either mindfulness-based relapse prevention or education sessions over several weeks, described in the University of Exeter’s KARE overview.

- Reviews describe short series of infusions or injections across a few weeks, with therapy delivered before, between, and after ketamine sessions, summarized in this broader PMC review of ketamine and substance use outcomes.

What does that mean in plain language?

- There is no single standard like “six infusions” for alcohol problems the way some clinics commonly use for depression.

- The data suggest two different paths can matter for some people: one carefully timed session inside a memory-reactivation framework, or a brief series paired with structured therapy—summarized in the alcohol-focused systematic review.

How fast people see changes

If you’re considering any intervention, you’re going to ask the obvious question: when would I feel a difference?

The answer from the studies is not “instant” and not “months later.” It’s usually somewhere in between.

- Reviews report that many participants describe rapid, short-term changes in mood and cravings within hours to days after dosing, similar to patterns seen in depression research, discussed in the Frontiers scoping review.

- In the AJP trial, the difference in alcohol-free days accumulated over the six-month follow-up, rather than showing up as a one-week blip, as reported in the KARE trial publication.

- In the harmful drinkers memory-reactivation trial, reduced drinking was observed over many months, suggesting that for some people the impact of a single session—when timed and structured—can persist, as reported in the Nature Communications trial.

But remember what these are: group averages. Some people feel little change. Others feel a strong early shift that fades. The studies describe patterns, not guarantees.

How long benefits last, and what relapse looks like in the better trials

Durability is the question everyone cares about and nobody can answer cleanly yet: does change hold, or does drinking creep back?

- In the KARE phase 2 trial, participants receiving ketamine accumulated more alcohol-free days over six months, with the strongest effect in the ketamine plus mindfulness-based therapy group; however, ketamine did not clearly reduce the overall relapse rate at 180 days compared with placebo, as reported in the KARE publication.

- In the harmful drinkers trial, the ketamine-after-reactivation group maintained lower drinking for nine months—unusually long for a single intervention—reported in Nature Communications (2019).

- Older ketamine-assisted psychotherapy cohorts often report one-year abstinence rates far above comparison groups, but modern reviews treat these as lower-confidence due to methodological complexity and limited standardization, discussed in this PubMed-indexed account of early ketamine psychotherapy models.

So the cleanest summary is this:

- Ketamine can extend periods of reduced drinking or abstinence for months in some people—especially when combined with therapy—summarized in the alcohol-focused systematic review.

- We do not yet have strong, consistent evidence that ketamine keeps people sober for multiple years without ongoing support; follow-up beyond a year is rare, and relapse still occurs, emphasized in this broader PMC review.

In the better trials, relapse patterns look less like a “cure” and more like a shift in the trajectory: delayed heavy relapse and more sober days overall—consistent with findings reported in KARE.

And the practical consequence is predictable: many people still need continued therapy, support groups, and/or other medications after the ketamine phase to maintain gains, a point emphasized in the Frontiers review.

Who seems to benefit most, and who struggles

The evidence base is not yet large enough to produce hard rules. But patterns show up.

Groups that seem to benefit more consistently

- Motivated treatment-seekers who have just stopped drinking. In KARE, participants were post-detox and abstinent at baseline; ketamine plus relapse-prevention therapy helped them accumulate more sober days during the vulnerable first six months, reported in the KARE trial.

- Heavy drinkers willing to engage in a carefully structured experimental protocol. In the harmful drinkers study, those who completed the memory-reactivation procedure showed large drops in drinking, reported in Nature Communications (2019).

- People who accept and engage in therapy around the ketamine sessions, especially skills-based relapse-prevention approaches—summarized in the alcohol-focused review.

Groups where evidence is weaker, or concerns are higher

- People with uncontrolled or severe mental health conditions often excluded from trials (e.g., untreated psychosis), which means limited data on safety and benefit—discussed in this broader PMC review.

- People seeking a quick fix without therapy. Most positive studies tightly couple ketamine with structured psychological support; ketamine in isolation is less studied and likely less reliable, emphasized in Frontiers.

- People with significant medical risks (e.g., serious cardiovascular issues) often excluded from trials; ketamine can transiently increase blood pressure and heart rate, noted in the PMC review.

In simple terms: ketamine looks most promising for people already engaged in change—freshly sober or actively reducing—who are willing to do real therapy around the sessions. It is not well studied, and may be riskier or less useful, in people with unstable mental/physical health or in approaches that strip away the therapeutic scaffold.

“Winning” vs “weak” protocols so far

It is too early to crown a single best protocol. But you can still see where the stronger signals are clustering.

Protocols with stronger signals

- Three IV infusions at 0.8 mg/kg paired with mindfulness-based relapse-prevention therapy (KARE): more alcohol-free days over six months than placebo combinations, especially in the ketamine plus mindfulness arm, reported in the KARE publication.

- A single IV infusion after targeted memory reactivation (harmful drinkers RCT): large and lasting decreases in weekly drinking over nine months compared with controls, reported in Nature Communications (2019).

- Older ketamine-assisted psychotherapy programs sometimes report very high one-year abstinence rates, but modern readers should treat these as hypothesis-generating rather than ready-made blueprints, discussed in this PubMed record.

Protocols that look weaker or more uncertain

- Ketamine delivered without structured therapy has much less clear support; the best results cluster around drug-plus-therapy packages, emphasized in the alcohol-focused systematic review.

- Tiny pilots combining ketamine with other medications (such as naltrexone) are not yet “successes” or “failures.” They are simply too small to adjudicate, as illustrated by this five-person pilot report.

If you’re trying to make sense of real-world protocols, the safest evidence-aligned takeaway is straightforward:

- Protocols that resemble the trials—sub-anesthetic dosing, limited sessions, monitoring, and integrated therapy—are closest to what we can actually defend from the data, emphasized in the Frontiers review.

- Protocols that drift far from the research (long stretches of frequent dosing without a clear therapeutic framework, vague goals, or very high dosing) are more speculative by definition and should be evaluated with extra care.

The pattern so far

The clinical details across studies point to a consistent shape: short ketamine courses, strongly paired with therapy, that can increase sober days and delay relapse for some people—without a clear long-term “cure” protocol, and without definitive answers yet on the best dose, schedule, or patient profile. That summary is consistent with the broader PMC review and the alcohol-focused systematic review.

Ketamine for Alcohol Problems: The Big Questions Science Hasn’t Answered Yet

What we know about dosing, duration, long-term results, and who benefits—and what remains uncertain

If you want certainty, ketamine research in alcohol use disorder can’t give it to you yet. What it can give you is a clear map of what’s known, what’s not, and where the evidence stops. The studies show promise in specific contexts—particularly when ketamine is paired with structured therapy—but they leave major questions unanswered: What’s the optimal dose? How many sessions work best? Do effects last beyond six months? Who responds and who doesn’t? The answers below come directly from what the clinical trials and systematic reviews can—and cannot—tell us.

The big unanswered questions—answered with the most honest Yes/No the evidence allows.

If you want certainty, ketamine research in alcohol use disorder can’t give it to you yet. What it can give you is a clean map of what’s known, what’s not, and where the evidence stops. The best summaries of that boundary-setting appear in this alcohol-focused systematic review and this Frontiers scoping review.

Is the optimal dosing known?

No.

Modern research typically uses sub-anesthetic IV dosing (often around 0.5–0.8 mg/kg), sometimes as a single session, sometimes as a short series. But no study has shown that one exact dose or schedule is clearly best for alcohol use disorder—a limitation emphasized in the alcohol-focused review.

- The KARE trial used three infusions at 0.8 mg/kg and reported more alcohol-free days, but it did not directly compare higher versus lower doses, as reported in the KARE publication (PubMed).

- The harmful drinkers trial used a single sub-anesthetic dose paired with memory reactivation and reported a large effect, but this is a highly specific design that has not yet been widely replicated, reported in Nature Communications (2019).

- Older and non-Western protocols sometimes used different dosing—including psychedelic-range approaches—but these are lower-confidence and not directly comparable to modern designs, discussed in this PubMed-indexed early ketamine psychotherapy record.

So yes: sub-anesthetic dosing is the modern research zone. But no: there is no agreed “best dose” for reducing drinking or preventing relapse.

Is the ideal treatment duration clear?

No.

There is no established “right number” of ketamine sessions for alcohol use disorder.

- Some studies use one infusion (with carefully timed memory work) and report long-lasting changes in harmful drinking, as reported in Nature Communications (2019).

- Others use three infusions with therapy and report more alcohol-free days over six months, as reported in the KARE trial publication.

- Older programs sometimes used one or two higher-dose sessions embedded in months of psychotherapy, but these are not modern standards, summarized in the alcohol-focused review.

No large trial has directly compared one vs three vs six infusions in alcohol use disorder to identify the best balance of benefit, risk, and cost. That’s why confident claims about a “magic number” of sessions go beyond what the evidence can currently justify—an issue noted in the Frontiers scoping review.

Do we have enough long-term data (6+ months, 12+ months)?

Partly for 6 months; no for long-term.

We have some medium-term data:

- KARE followed participants for six months and found more alcohol-free days in ketamine-treated groups, especially when combined with mindfulness-based therapy, reported in the KARE publication.

- The harmful drinkers trial tracked outcomes for nine months and reported sustained reductions in alcohol use in the ketamine-after-memory-reactivation group, reported in Nature Communications (2019).

But beyond that, the evidence thins out fast:

- Few modern ketamine-and-alcohol trials follow people for a full year or more, and those that do tend to be small or older and less rigorous—limitations emphasized in Frontiers.

- We do not have large, high-quality evidence showing ketamine-based approaches keep people sober for multiple years without ongoing support, noted in this broader PMC review.

So the honest line is: promising 6–9 month data in some settings, uncertain durability beyond a year.

Do we know the best patient subgroups?

No.

The trials and reviews offer hints, not rules.

Hints that exist

- People freshly abstinent after detox who enter structured therapy may be good candidates. That exact population benefited on alcohol-free days in KARE, reported in the KARE trial.

- Heavy harmful drinkers motivated enough to participate in controlled research may also benefit, as seen in the memory-reactivation trial.

- People willing to engage deeply with therapy around dosing appear to align best with where the evidence is strongest, consistent with discussion in the broader PMC review.

Big gaps

- Trials often exclude people with certain mental health conditions (e.g., psychosis) or serious medical problems, leaving limited safety/benefit data for those groups—discussed in the alcohol-focused review.

- We lack strong subgroup analyses by age, sex, duration of alcohol use disorder, and co-occurring substance use that would allow confident “this subgroup benefits most” claims—emphasized in Frontiers.

Right now, there is no evidence-based “perfect candidate” profile. Decisions remain case-by-case, guided by general principles rather than subgroup proof.

Are the mechanisms proven, or still speculative?

Partly understood, partly speculative.

We have good reasons to think ketamine’s effects involve plasticity, mood, and learned patterns:

- Ketamine’s glutamate-linked plasticity effects are well documented across psychiatry and substance use contexts, summarized in the BJPsych Open systematic review.

- The harmful drinkers trial supports the idea that timing ketamine around memory reactivation can change how alcohol-linked learning influences behavior, reported in Nature Communications (2019).

- Reviews propose plausible pathways: weakening cue-driven pull, improving stress tolerance and mood, and enhancing therapy during a plasticity window, discussed in the broader PMC review.

But:

- We do not have direct human evidence that “this specific neural change caused this specific drinking change.”

- Multiple mechanisms likely operate together (mood effects, anxiety effects, reward processing, therapy enhancement), and the balance is still unclear—discussed in this ScienceDirect review of ketamine and addiction mechanisms.

So the mechanism story is plausible and partially supported, but not nailed down in a cause-and-effect way.

Is relapse prevention after stopping ketamine well understood?

No.

Relapse prevention after ketamine remains one of the biggest unknowns.

What we know

- In KARE, ketamine-treated groups accumulated more sober days over six months, but relapse still occurred and overall relapse rates at 180 days were not sharply different from placebo, reported in the KARE trial.

- In the harmful drinkers study, reduced drinking persisted for nine months, but there is no evidence of indefinite protection after the course, reported in Nature Communications (2019).

- Older ketamine-assisted psychotherapy programs reported high one-year abstinence, but these results are treated cautiously today due to lower confidence in methods, discussed in this PubMed-indexed early record.

What we do not know

- How long benefits last without ongoing therapy or support.

- Whether “booster” sessions meaningfully maintain gains or simply add cost and risk.

- What repeated use over years does to risk profiles; bladder and cognitive harms are documented in heavy recreational use, and reviews flag the need to watch these issues in clinical contexts as well, discussed in the alcohol-focused review.

Clinically, the implication is straightforward: if ketamine is used, it should be embedded inside long-term relapse prevention—therapy, support, lifestyle redesign, and sometimes standard medications—rather than treated as a standalone shield. That conservative framing aligns with the Frontiers scoping review.

Overall: what the evidence allows you to say

- Optimal dose and duration: not yet defined.

- Long-term data: some 6–9 month results; very limited beyond a year.

- Best patients: no clear profile; motivated people in structured therapy show the strongest promise.

- Mechanisms: plausible and partly supported, not fully proven.

- Relapse prevention: still uncertain; ketamine is best treated as one tool inside a longer plan.

The Future of Ketamine Research for Alcohol Problems: What’s Coming and What’s Still Needed

Larger trials, longer follow-ups, and the questions researchers are racing to answer

The current evidence base is small—most trials enrolled fewer than 100 people. The systematic reviews are unanimous about what comes next: bigger studies, longer tracking, and clearer answers about who benefits and why.

The Largest Trial Yet: MORE-KARE

The UK is running a larger multicenter trial called MORE-KARE (Mechanisms Of action and Reduction of alcohol rElapse—Ketamine Assisted REhabilitation), targeting approximately 280 participants across multiple sites. This would be the largest ketamine-for-alcohol trial to date—roughly three times the size of the previous largest study (KARE Phase II, n=96).

MORE-KARE is designed to answer mechanistic questions the earlier trials couldn’t: how does ketamine change drinking behavior, and can those brain changes predict who will respond? Results aren’t available yet, so this can’t be used as evidence—only as incoming data that may clarify or complicate the current picture.

What Researchers Say Is Missing

The systematic reviews published in 2022-2025 converge on several critical gaps:

- Dose-finding studies are absent. No trial has directly compared different ketamine doses (e.g., 0.5 mg/kg vs 0.8 mg/kg vs 1.0 mg/kg) to determine optimal dosing for alcohol outcomes. Current protocols use doses borrowed from depression research or older psychedelic-era models, not from systematic alcohol-specific optimization. This gap is emphasized in the alcohol-focused systematic review (Kelson et al., 2023).

- Long-term follow-up is rare. Most trials track participants for 6-9 months maximum. We don’t know if effects persist beyond a year, whether relapse patterns stabilize or worsen, or what happens with repeated courses over multiple years. The Frontiers scoping review (Goldfine et al., 2023) explicitly calls for multi-year follow-up as a priority.

- Subgroup analyses are underpowered. Current trials can’t definitively answer “who responds best?” because samples are too small to detect differences by age, sex, severity, psychiatric comorbidity, or treatment history. Identifying predictive biomarkers or clinical profiles requires much larger datasets, as noted in the American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse review (Rathore et al., 2025).

- Therapy integration protocols vary wildly. KARE used mindfulness-based relapse prevention. Dakwar used motivational enhancement therapy. Das used memory reconsolidation techniques. We don’t know which therapy approach works best with ketamine, or whether specific combinations outperform others. Head-to-head therapy comparisons haven’t been done, a limitation discussed in the Drug and Alcohol Dependence review (Garel et al., 2022).

- Safety monitoring for repeated use is incomplete. Heavy recreational ketamine use is associated with bladder damage and cognitive changes. Clinical trials use much lower doses, but we don’t have data on what happens with long-term intermittent medical use (e.g., quarterly “booster” sessions over 5-10 years). The Cureus systematic review (Kelson et al., 2023) flags this as a critical safety gap.

What Would Actually Move the Needle

The field needs three things to move from “promising” to “practice-ready”:

- Large pragmatic effectiveness trials (500+ participants) across diverse clinical settings—not just research-intensive academic centers. Can ketamine work in community treatment programs, rural clinics, and under-resourced settings? Unknown.

- Standardized protocols with direct comparisons. One trial testing: ketamine alone vs. ketamine + therapy A vs. ketamine + therapy B vs. therapy alone, with matched doses and schedules. This would finally answer whether the drug or the context drives outcomes.

- Multi-year naturalistic follow-up studies tracking real-world outcomes in people who received ketamine for alcohol problems 2, 5, and 10 years earlier. Relapse rates, quality of life, adverse events, and whether people needed ongoing treatment.

The Honest Timeline

Even if MORE-KARE publishes in 2026-2027 and shows strong results, we’re still years away from having the evidence base needed for widespread clinical adoption. Ketamine for alcohol use disorder would need:

- Regulatory review and approval pathways

- Insurance coverage decisions

- Training protocols for clinicians

- Safety monitoring standards for long-term use

The optimistic scenario: 5-7 years to move from “experimental” to “evidence-based option for specific patients.”

The realistic scenario: 10+ years to answer the hard questions about who, how, and how long.

FAQ: Ketamine for reducing alcohol cravings and problem drinking

Medical disclaimer: This is educational only and does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment clearance. Ketamine for alcohol use disorder is not FDA-approved and remains experimental.

1) What do the 16 studies show overall?

Across the full set of studies, the evidence is encouraging but mixed: some trials show meaningful reductions in drinking, others show smaller or inconsistent effects, and at least one high-quality trial shows no clear alcohol benefit.

2) Is ketamine “proven” to treat alcohol problems?

No. The strongest trials show a real signal, but there isn’t one standardized protocol, and results vary by study design, population, and how therapy is paired with dosing.

3) What do the strongest randomized trials actually find?

One of the best placebo-controlled trials (KARE Phase II) found more alcohol-free (abstinent) days over 6 months for ketamine vs placebo, with the largest benefit when ketamine was paired with mindfulness-based relapse-prevention therapy; relapse rates (yes/no) did not clearly separate groups.

Another well-controlled trial (Dakwar 2020) found higher abstinence, fewer heavy drinking days, and longer time to relapse versus an active control when ketamine was paired with motivational enhancement therapy.

4) Does ketamine eliminate cravings or “flip an off switch” for drinking?

It should not be treated as a guaranteed cure. The more realistic model is that ketamine may create a temporary window where cravings are quieter and new patterns are easier to learn—then the window closes, and what happens after (therapy, routines, environment) determines whether gains last.

5) Who were these studies done on?

Clinical trials enrolled people with hazardous or dependent drinking—not occasional social drinkers.

6) When does ketamine seem most likely to help?

The strongest pattern in the evidence is that outcomes look best when ketamine is paired with structured, skills-based therapy (for example, relapse-prevention approaches or motivational therapy), rather than treated as a standalone event.

7) How might ketamine reduce cravings and drinking?

Ketamine is not framed as a daily “anti-craving pill.” The main hypothesis is that it opens a short plasticity/learning window (hours to days, possibly longer) that can make behavior change and therapy “stick” more easily.

A second mechanism explored in a notable trial is memory reconsolidation: alcohol-related memories/cues are reactivated, then ketamine is given during a time window when those memories may be more modifiable, potentially weakening cue-driven urges.

8) What is the “memory reactivation” study people talk about?

In a randomized trial in harmful drinkers, ketamine given shortly after alcohol-memory reactivation was associated with a large, lasting reduction in weekly drinking over 9 months (about a 50% reduction reported in the summary), but this is a specialized setup and may not translate cleanly into typical clinical care.

9) How does ketamine compare to standard alcohol medications like naltrexone?

Standard medications are typically steady, ongoing tools (daily/regular dosing) and have been tested in larger, longer programs than ketamine has so far.

Ketamine research protocols are usually episodic (often one to three infusions) and the most promising approaches embed dosing inside structured therapy to use a short change window.

10) Does combining ketamine with naltrexone improve alcohol outcomes?

A high-quality randomized trial in people with comorbid depression and AUD found no significant group differences in alcohol abstinence or craving, and naltrexone did not appear to change alcohol outcomes in that study.

The broader takeaway presented is that “ketamine + medication” combinations remain early and not proven at scale.

11) What dosing and treatment protocols were used in the studies?

Across the more credible trials and reviews summarized, ketamine is typically delivered in short courses at sub-anesthetic doses and usually alongside therapy.

Examples listed include: three IV infusions at 0.8 mg/kg over 40 minutes in KARE; a single IV infusion at 0.71 mg/kg over 52 minutes in Dakwar 2020; and reviews describing common sub-anesthetic IV ranges (often around 0.35–0.8 mg/kg) plus some older IM protocols in the 2–3 mg/kg range.

12) What do these studies suggest about safety (in monitored research settings)?

Two randomized trial summaries report no serious adverse events.